AFFSOONGAR ON BEING THE SLAYER, THE ENCHANTER, THE UNSHAMED.

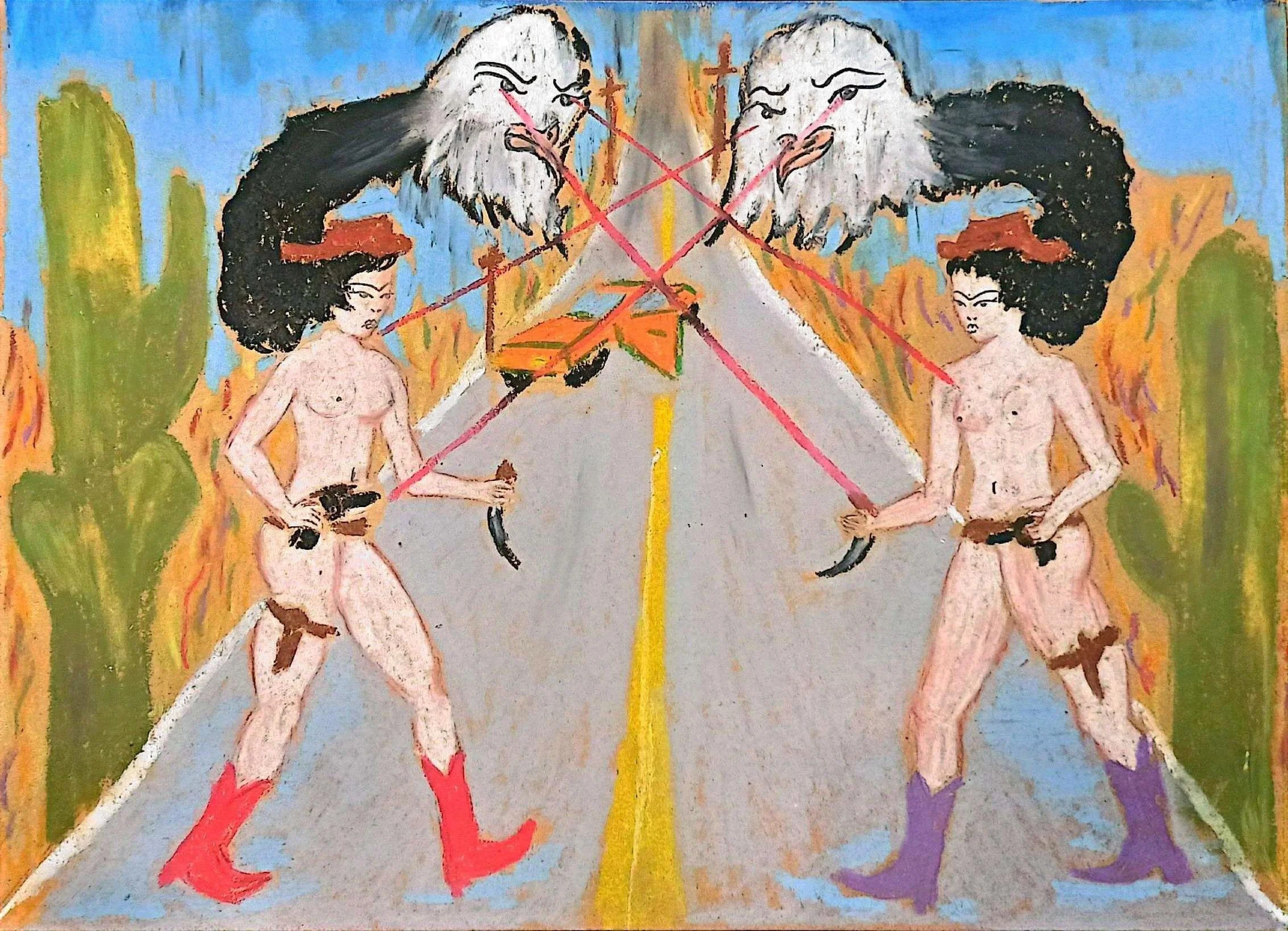

For Affsoongar, painting is a portal: one through which wounded heroines wield daggers, menstruation flows in bright visceral colours, and the female form returns to its rightful place: untamed, unapologetic, and very much alive. Her creatures are mythic, but they are not fantasy. They are the remnants of shapes long censored, the futures we haven’t dared to live yet. Raised under the shadow of censorship in Tehran but fluent in digital culture, she taught herself everything. Her work lives between hunger and refusal, softness and fury. She paints apples into breasts and mouths into prayers. Her scenes are not erotic, they’re exposed. Not because they want to seduce you, but because they don’t care if you’re seduced. There is no hierarchy in her imagination and her refusal to render shame makes her experiments all the more necessary. When asked what she wants her art to do for future generations, she doesn’t hesitate: “Set their soul on fire.”

AASI: Your artist name, Affsoongar, means “the enchanter.” What does enchantment mean to you in a world that constantly tries to reduce, label, and censor?

AFFSOONGAR: It means I can be whoever I want to be, without shame, without limits, and without any higher power defining who I can become. I can be the one who saves or who is saved. I can seduce or be innocent, sometimes at the same time. But above all, I am a powerful woman in all of these narratives. That’s the real magic behind my work.

AASI: Much of your work draws on feminine mythology: figures who are bleeding, slaying, or shapeshifting. What does myth allow you to express that realism cannot?

AFFSOONGAR: Myth lets me expand beyond what’s visible, beyond what’s “allowed.” The figures I paint don’t exist yet—they can’t. Especially not in the country I live in. Iran is ruled by patriarchy. Myth becomes my portal to imagine and manifest women who slay, who hold power. These women might not exist in public life, but in my work, they take form.

AASI: Your creatures are often wounded, bare, and fearless, not sexualized, but exposed. Do you think bareness can be a political gesture?

AFFSOONGAR: Definitely. Especially here, where shame is used as a tool to control. I’m not promoting bareness for its own sake. What I know is that shame has been used to manipulate and distract people from their true power, especially women. My creatures don’t wear shame. That’s their rebellion.

AASI: What Persian myths or archetypes have you consciously reimagined or rejected through your work?

AFFSOONGAR: I grew up surrounded by stories of male heroes. But if anyone in this world has superpowers, it’s women, because of what we physically and emotionally endure. I never saw that reflected in any of the Persian myths I was raised on. So when I started painting, all I wanted to paint were women with power. Women holding guns. Women being worshipped. I’m creating what never existed for me.

AASI: How does being self-taught in Iran and navigating censorship while immersed in digital visual culture shape your defiance?

AFFSOONGAR: It’s hard to be an outsider, but I don’t mind. Every day I teach myself something new, technically, emotionally. Each painting deepens the language I’m building. I don’t follow rules. I build my own world.

AASI: Do you see your paintings as offering an alternate timeline—speculative futures or ancestral pasts, for how we might live differently?

AFFSOONGAR: Absolutely. A world without shame is an interesting place to live in, even if we never fully reach it. I like that I can paint it. Maybe I can offer a taste of that shameless world, even for a few seconds, to whoever looks at my work.

This conversation was conducted as part of AASI’s ongoing editorial archive on speculative embodiment, underground image-making, and the reclamation of cultural futures through aesthetics of refusal.