TOWARDS A LIVING ARCHIVE: A CONVERSATION WITH SHAYAN SAJADIAN

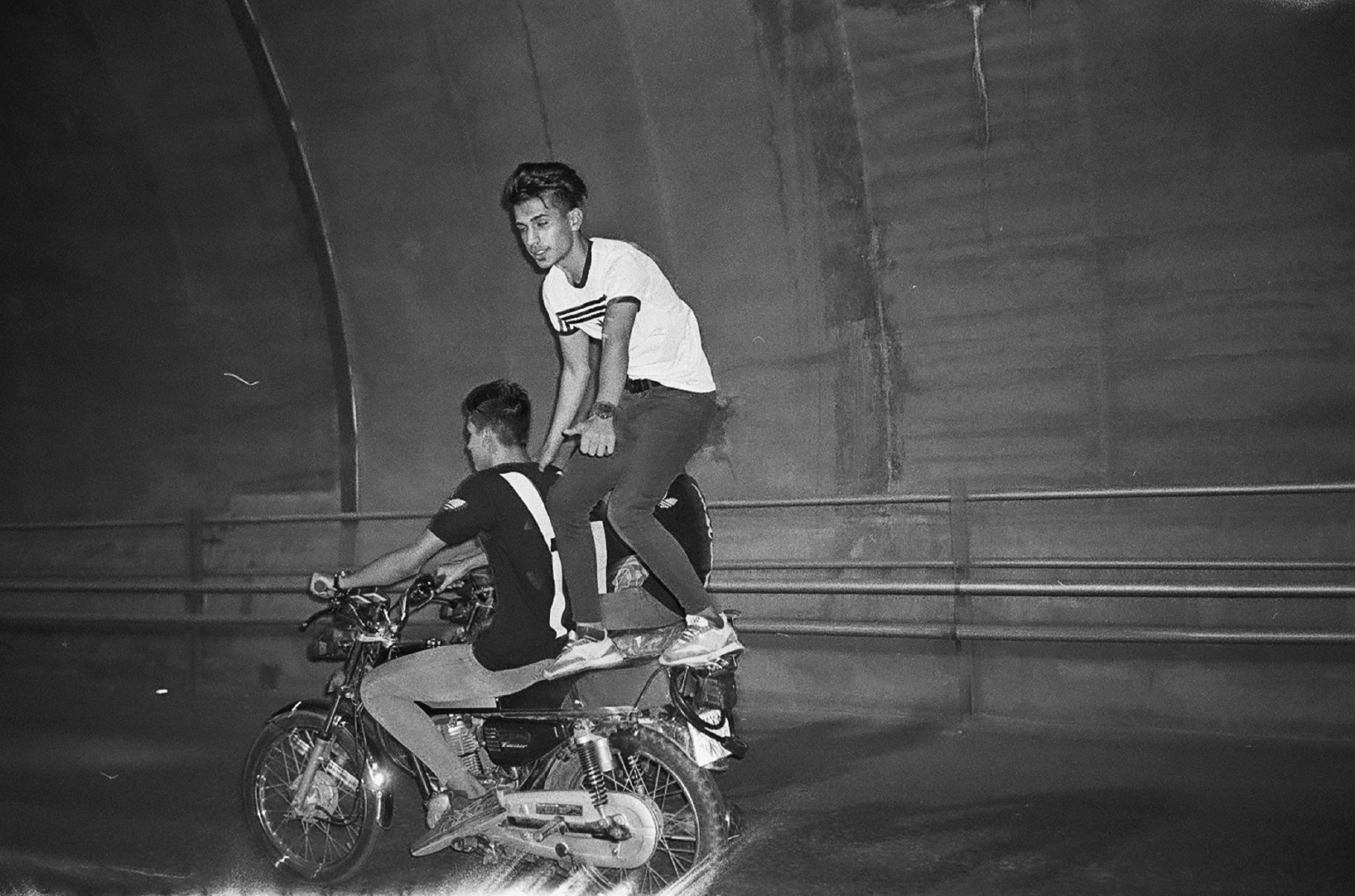

Shayan Sajadian is a documentary photographer based in Iran whose lens resists spectacle and instead turns toward the fleeting, the overlooked, and the intimate. With a deep interest in working-class life—particularly among young men—his work gently disarms dominant narratives of masculinity and state-produced identity. Shayan’s images move through contradiction: fragile bravado, gentle rebellion, worn beauty. His photography doesn’t seek to explain or affirm: it dwells instead in what is felt and what is nearly missed. In a cultural climate shaped by censorship, policing, and symbolic fatigue, his practice stands as both document and offering: a quiet archive of the margins. Through long-form witnessing, Shayan crafts visual meditations that disrupt tropes and let the contradictions of a person, a space, or a time speak for themselves.

AASI: Your work often subverts dominant scripts about gender, portraying men with softness and women with strength. As a male photographer navigating this from inside Iran, how do you stay accountable to the communities you portray? What risks do you navigate when you offer tenderness in place of toughness?

SHAYAN: Iran has long been described as a patriarchal society, but over time, with widespread social change, the roles of men and women have undergone significant shifts. For example, Iranian women, through perseverance and resistance, have made remarkable progress in claiming their place across various dimensions of society as full human beings.

But I didn’t want my work to get entangled in slogans or gender clichés about women and men. I tried to depict the truth I see in a different way. I believe both women and men have been wounded by these differences, in different forms. My intention isn’t to compare them, but to portray them in a way that while you see the contrasts, you also feel something else in the background.

You might see muscular, seemingly aggressive men, but also feel softness and vulnerability within them. You might see women who, despite all the gaps and challenges they've faced, continue to resist and live.

Portraying these themes this way comes with risk. There's always the chance the images get trapped in slogans or stereotypes. But I’ve always tried to reduce that risk, or in some cases, use the surface-level clichés as a cover to reveal something deeper, to either complicate or contradict them.

You know, I feel like my only responsibility is to pursue what I love while still showing reality. The people and themes I care about—I want to capture them differently. In a way that lets you both witness and imagine something through documentary photography.

AASI: One of the foundational principles of our work is resisting the fetishization of pain and trauma. How do you ensure that your subjects are not reduced to symbols of suffering?

SHAYAN: Aesthetics come in many forms. I try to make sure that beauty exists in my photos no matter what. You can take a beautiful photo of a difficult subject without glorifying or promoting ugliness. Of course, people interpret things differently, and sometimes misinterpret them. You can’t please everyone. But I always try not to make something harmful look beautiful. That said, there are things society wrongly deems ugly, and I try to show that this perception is flawed.

One of the things I strive for in my photos is to make people willing to look at the things they usually avoid—things they don’t want to see. That confrontation is important to me.

Personally, I’ve shifted my approach. I used to respond emotionally and impulsively to events—but I realized that’s not my path. I’m not meant to be a photojournalist. I want to take the long view, to be able to witness and reflect changes over time. I think that’s the role of artists.

AASI: Within a culture of deep censorship, silence can become both survival and strategy. What are the silences you choose in your work—and what do they cost you?

SHAYAN: I try not to censor or edit subjects while shooting. But the timing of when I share the image. that’s crucial. Sometimes, you can capture a truth that serves as testimony for the future. And if sharing it now can have an impact, then it’s worth the risk.

These challenges are always there. I’ve faced risks from the areas I’ve entered to shoot, and also from authorities who are sensitive to what I document. I’ve had my gear stolen. I’ve been attacked by criminals, even threatened with assault. Police have detained me during shoots or called me in for questioning, something many photographers in Iran have experienced.

AASI: Some critics have accused your work of aestheticizing violence. How do you respond to that kind of framing?

SHAYAN: Until I was 18 or 19, I wasn’t aware of the broader society I was living in. It was only in university that I began to see the social landscape more clearly and became curious about people I hadn’t encountered before. I started photographing them intuitively.

Over time, I realized many of my subjects were men and I began to see how much their bodies could reveal about who they were, or who they pretended to be.

If you look closely, you’ll notice location is always important in my photos. The background tells you something about their environment. These surroundings, with their subcultures, have influenced their lives.

Who is a man? In our culture, he’s supposed to be tough, to drink from a young age, to never cry, to fight when necessary, to carry a knife. But behind all that violence, there are vulnerabilities. I try to show that too.

AASI: Being a male photographer in Iran comes with limits, especially when photographing women. Do you view your gender as a limitation or as a lens?

SHAYAN: Being a man has made it harder for me to photograph women, especially in the areas I work in, where people are traditional and sensitive to this.

You know, I’m from the middle class. But this lower-income class, their lives were invisible to me for a long time. I didn’t see them. Their lives felt different, even mysterious, and I’ve made it my mission to enter their world, to live among them and document them so that others like me might see them too.

I can’t easily say what they see in me. For many, my work is confusing, maybe even pointless. And maybe they’re right; maybe I can’t change anything. All I can do is what I love: document, and hope it gets seen.

AASI: What’s one image you carry in your memory because you couldn’t take it?

SHAYAN: There are so many moments I’ve missed, photos I didn’t get to take. I carry the regret of those missed opportunities, but I move forward, hoping to miss fewer next time and capture more.

AASI: The mission of ÂSI is to build decentralized, counter-archival memory systems for future generations. What do you hope your work can offer those looking back at this moment?

SHAYAN: I can’t say for sure—I’m still working, still learning. It’s too early for me to have answers for everything I do. But I try to document as much as I can, in the hope that some of it might be useful for history someday.

My work shows only a fragment of Iranian society. It can’t stand alone. But maybe, collectively, the work of many photographers can eventually offer a fuller picture, something that resonates with future generations.

Maybe the best thing I can show is the sheer wonder of human life. How different two people’s lives and logic can be. Once a photo is made and finished, the work is done. Everyone sees something different in it. But the greatest gift photography has given me is the experience of being among people, going into their world and sharing space with them. That might be the greatest gift of my life.

This conversation was conducted as part of AASI’s ongoing editorial archive on speculative embodiment, underground image-making, and the reclamation of cultural futures through aesthetics of refusal.